Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial

On 17 August 1942 flying fortresses of the Eighth United States Bomber Command made their first independent raid on Europe, dropping 18 tons of bombs on the railway yards at Rouen. Thereafter, American airstrength continued to grow in England, Scotland and Wales, necessitating more than one United Srates cemetery. The Chief Quartermaster considered constructing a major cemetery on a 65-acre tract of land at Madingly Hill, adjoining Madingly Wood, about 3 miles northwest of Cambridge.

Preliminary arrangements for the development od the area were completed in October 1942. Several months later the Lands Directorate of the British War Office reported that both administrative and financial approval had been recieved. Furthermore, all clearances from other ministries- particularly the Ministries of Agriculture, Health, and Works and Planning- had been obtained. The entire matter awaited only a firm United States policy for acquiring the land. This policy was announced in a directive issued by the Memorial Division, OQMG, on 14 July 1943. The War Department had no objection to the purchase or rental of land for cemeteries, but it should be understood that such land should not be acquired on a permanent basis. “As it is expected, ” the directive read, “to return remains to the United States after the cessation of hostilities, no arrangements should be made to establish permanent cemeteries until after cessation of hostilities when a definitive policy will be established“. Consequently on 1 August 1943, Brigadier General Littlejohn recommended that steps be taken to activate the Cambridge Cemetery on a temporary basis.

GPS location Cambridge American Temporary Military Cemetery.

Several British agencies at once became concerned about the proposed cemetery. The Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, asked that university authorities be consulted as to style, layout, and architecture so that the cemetery would be in keeping with the tone and tradition of its surroundings. An official of the Lands Office of the British War Office explained that the Cambridge Preservation Society was prepared to offer the services of an eminent British architect to design and lay out the cemetery. “I should have thought“, he wrote, “that an assurance to the Society- if you are prepared to give one- that your plans for the layout of the cemetery will be available for inspection by the Society if necessary, and that without committing yourselves you would be prepared to consider any suggestion from the Society.” The Office of the Chief Quartermaster agreed to listen to the suggestions of all interested British agencies, but reserved the right to lay out the cemetery according to War Department regulations. Final arrangements were made during the next 3 months, and the Cambridge Cemetery was activated on the second anniversary or Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1943.

A beautification program was started almost at once; and an office building, a chapel, and reception and processing buildings were erected during the winter of 1943. In FEbruary 1944, the horticultural expert of the Imperial War Graves Commission was sent to Cambridge to assist in the development of the area. The first indication that Cambridge was being considered as a permanent cemetery came on 8 March 1944. On that day, Major General Lee wrote Brigadier General Sir Henry Page Croft, Baron of Bournemouth, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for War, that “the strong bonds of sentiment which tie our people with Cambridge are so compelling that I feel the Madingly Cemetery should be chosen as a permanent location for the burial of our honored dead. This plan will call for the development and beautification of apporximately 39 acres to meet our full requirement.” Several days later he wrote a similar letter to the owner of the Madingly property, Dr Rosemond E. M. Harding. In her reply, Dr. Harding wrote as follows:

“I have given this matter of the cemetery a great deal of thought. Unfortunately, under the terms of my father’s will, I’am not sble to make you a present of the 39 acres, but I can assure you that I have decided to withdraw any objections to your acquiring this land.”

Lord Croft wrote the next day that the owner and the trustees of the estate “regarded it as an honor that your gallant men should rest permanently in their midst”. There were, however, two points that Lord Croft wanted understood. First, the cemetery should be as beautiful as possible. The best architects in England should be consulted to make the general layout blend into the rather exceptional English character of the section. In other words, he would welcome “a beautifully planned garden with graves in it, rather than a crude cemetery with flowers in it, as so many of our own unfortunately appear to be”. Second, if the 39 acres still should not be enough, the cemetery should not be extended into Madingly Wood, but a new burial ground should be selected elsewhere.

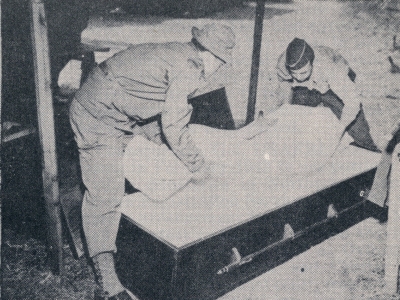

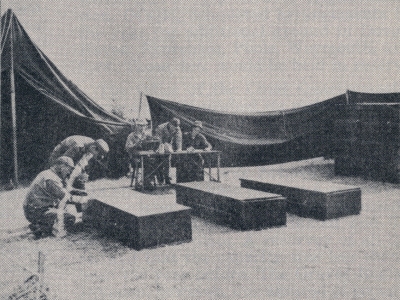

- Processing bodies in the Marshalling Areas.

Dr. Harding had asked also that the farmer on the property be adequately compensated, for Madingly was his only means of support. Major General Lee agreed that the farmer would be taken care of promptly and that the United States forces would not need more than 39 acres. He assured Lord Croft at the same time that everything would be done to maintain beautiful surroundigs and added, “as the planting of shrubs and trees is supervised by the Imperial War Graves Commission,… such matters are being forwarded to Sir Fabian Ware.” Sir Fabian wrote on 8 May that Professor A. E. Richardson of Cambridge University had agreed to serve as architectural consultant for the cemetery.

Several weeks later Lord Crof outlined the procedure to be followed in acquiring the land. “We are about to buy the site at Madingly,“he wrote, “and I think that the simplest method of procedure would be to leave the freehold vested in the Secretary of State for War. This avoids throuble of a second conveyance and sidesteps any legal difficulties that might crop up.” An instrument should then be prepared, he said, giving the appropriate American agency the right to burial in perpetuity. Finally a member of the Imperial War Graves Commission and members of the Graves Registration and Inquiry Service should be appointed to a board, consisting also of United States officers, to keep in contact with the landowner, the Ministry of Heatlh, and the Royal Fine Arts Commission.

By 31 May 1944 more than 300 burials a month were being made at Cambridge and approximately 3,680 bodies had been buried in the cemetery. The Engineer of the Western Base Section reported, however, that the plot arrangement had been laid out without reference to permanent landscaping and did not conform to the plan prepared by Professor Richardson. Because burials were being made in locations ordered by the Graves Registration and Effects Division, a definite decision should be reached as to which plan should be followed. He also wanted to know to whom Professor Richardson was responsible, who had the authority to accept his plan, who was responsible for future planning, and who could authorize construction. In the absence of information to the contrary, he would operate on the premise that OCQM was the lowest authority that had the right to decide upon operations at the cemetery. Although he was never given a definite answer, he was led to understand that the landscaping committee of the Cambridge Cemetery (which included Professor Richardson, as well as the Camouflage Coordinator, Office of the Chief Engineer, and the Executive Officer, Graves Registration Division) was responsible to OCQM abd tgat tge Chief Quartermaster was directly responsible to the Theater Commander for the operation of the cemetery.

- Processing bodies in the Marshalling Areas.

By D-Day a number of legal technicalities had arisen, which the Adjudant General believed should be settled if negotiations with the British were to be continued. Specifically, the Adjudant General wanted to know if United States had the right at that time to establish Cambridge as a permantent cemetery. The Judge Advocate General ruled that the Theater Commander was not empowered to take such action. “This matter,” he wrote, “involves questions of both policy and law. The formulation of policy for the operation of graves registration services outside Continental United States is a function of OQMG, which has announced that only temporary cemeteries should be established… and that no action should yet be taken to establish permanent cemeteries. Overseas commanders are instructed that no real estate will be acquired in fee by United States Army forces without prior approval of the War Department. A perpetual easement, although not a fee title, is so akin thereto that it should be regarded as coming within the prohibition of the War Department regulations.” G-4 and OCQM agreed, however,that nothing stood in the way of using Cambridge as a temporary cemetery and that negotiations of with the British should continue. Major General Littlejohn wrote about 10 days later that any agreement signed with the British should give OCQM the right to burial in perpetuity; the right to construct buildings, roads, walks, flagpoles, utilities, and other appurtenances; and the right to exhume bodies for repatriation or concentration elsewhere, with the understanding that all land so vacated would be released from the agreement. Major General Le approved these terms and submitted them to Lord Croft, saying that they might eventually form the basis for a permanent agreement. He asked that OCQM be consulted on all details until some other agency was established.

On 5 November 1944 the Cambridge Board of the English Speaking Union offered its assistance to the relatives and friends visiting the graves of American soldiers at Cambridge. “The visits to the cemeteries,” the Union wrote the United States Embassy, “will probably be officially handled by your organization, as after the last war, but there may possibly be other parts of the country the visitors might wish to see.” When the letter was sent to OQMG, the Chief of the Memorial Division replied that American dead would be returned to the United States if the next of kin of 70 percent of the dead in any one theater requested. “However,” he continued, “if 70 percent of the next of kin of the dead buried in the United Kigdom did not desire the remains returned, the bodies should be moved to Brookwood for final interment.” In January 1945 the letter from the English Speaking Union was returned to the European Theater and came , for the first time, to the attention to the Chief Quartermaster. Major General Littlejohn wrote that, contrary to the opinion of the Office of the Quartermaster General, he firmly believed that Cambridge would be retained as a United States cemetery, although the final decision rested with the Congress. To the Chief of the Graves Registration and Effects Division he wrote that the Memorial Division “without having any knowledge whatsoever of the problem in the Theater has endeavored to discuss matters about which its knows nothing. Therefore, in the future, please let us handle our own problems here in Europe, as I’am sure we can find a satisfactory solution without bothering OQMG.”

- Processing bodies in the Marshalling Areas.

The War Department repatriation plan, published on 8 September 1945, provided that the 9,167 American soldiers buried in the United Kingdom be interred at Cambridge. This meant that the 3,633 bodies buried at Lisnabreeny would be buried with the 5,386 bodies already interred at Cambridge. The Office of the Quartermaster General announced in June 1947 that Cambridge had been selected as a permanent American Cemetery.